There’s a place not far from Columbia, South Carolina, surrounded by enormous trees, where a person loses all sense of proportion. A sweetgum tree, for example, that from a distance appears tiny, turns out, upon close inspection, to be quite tall. The girth of the trees found here is not the only natural feature that impresses visitors. At least as impressive, competition for sunlight and nutrients from floodwaters has produced a canopy that ranges in height up to 150 feet, making a person feel small when hiking, canoeing or kayaking in Congaree National Park.

Below bluffs that border the Congaree River floodplain stand loblolly pines 10 feet in circumference and 150 feet tall. According to park rangers, the pines found here are taller than the trees, which provide natural canopies in Japan and much of Europe.

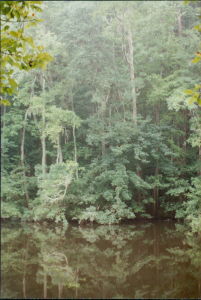

Weston Lake in the National Park, as seen from the Boardwalk. An intricate reflected pattern of shadow, water and fallen leaves embroiders the lake.

Early in this nation’s history, old-growth bottomland forests occupied the floodplains of many southern rivers. One by one, those forests were felled. Today, one of the last of these is the Congaree Swamp, which is located 18 miles southeast of Columbia.

The Swamp occupies the floodplain of virtually the entire length of the Congaree River, which is formed in Richland County with the confluence of the Saluda and Broad rivers. Some 60 river miles downstream, the Congaree loses its identity as it joins with the Wateree River to form the Santee River. With its characteristic flooding currents, the meandering Congaree can and does occasionally cut off one of its many river bends to form an oxbow, such as Weston Lake.

The Congaree River southeast of Columbia meanders along, switching back and forth in a course that covers 60+ miles. Along the way, giant sweetgum trees, as well as blackgums, sycamores, southern hackberries, oaks, ashes and hickories dominate the landscape.

History

When westward expansion during colonial times reached the Congaree Swamp, settlers found a forest of enormous hardwoods so thick it blocked out sunlight and kept the forest floor virtually free of underbrush. Settlers also encountered the Congaree Indians, a people who lived peaceably among the huge trees and who supported themselves by fishing, trapping and hunting. At that time, cougars, bears, elk and wolves were plentiful in the area.

Around the time of the American Revolution, some land alongside the Congaree River was being cultivated. However, the cost of clearing land and building dikes to protect crops from flooding proved over time to be prohibitively expensive.

The Congaree Swamp Boardwalk. The largest stand of loblolly pines in the world grows in Congaree National Park, located near Columbia, South Carolina.

In 1895, the Santee River Cypress Lumber Company began acquiring choice tracts of South Carolina swampland that contained cypress trees. By 1905, the company owned more than 10,000 acres of bottomland. Cypress harvesting soon followed the land purchases, and logging took place all along the waterways, sloughs and ponds where cypress trees grew. The average age of the trees that were cut was between 500 and 600 years. However, because the timbering operation proved to be unprofitable, the Congaree Swamp remained relatively undisturbed and virtually unknown except to a handful of hunters and anglers.

Protection of the Congaree floodplain was discussed intermittently during the 1950s. In 1963, the National Park Service issued a report, which stated: “The virgin forest and large trees of the Congaree give the area national significance.” Accompanying the timber industry’s renewed interest in Congaree’s massive trees around 1969, conservation groups began lobbying for protection of this natural resource.

In 1974, the Congaree was designated a National Landmark, which was a first step toward preservation. Just before adjourning late in the bicentennial year, the U.S. Congress designated 15,135 acres of bottomland as the Congaree Swamp National Monument. President Gerald Ford signed the bill into law October 18, 1976. Congress changed the park’s name to Congaree National Park and added 4,600 acres to the park on November 10, 2003.

What To See And Do.

A marked canoe trail invites visitors to explore Cedar Creek, which runs through the National Park. Here, water flows like black molten glass between forested banks that are thick with tupelo, holly and cypress trees.

You may on occasion encounter otters carousing at the river’s edge. Swimming back and forth across the stream, otters seldom take notice of your presence. They can at times be spotted cruising upstream, poking their whiskered snouts out of the water, peering around with huge black eyes, then diving quickly beneath the surface.

During one foray into the Congaree, I was greeted by a pileated woodpecker. A brilliant spark of red whizzed by my head, and then I heard a chuckle. Sure enough, it was a dead ringer for Woody Woodpecker. Later I learned that the park is home to all eight species of woodpeckers found in the Southeast. On a mild spring day, park rangers say, the woodpeckers’ investigative pecking resembles the noise made by a jackhammer.

Enclosed by the Congaree Swamp, you begin to hear a symphony of different sounds, many reminiscent of the jungle. Raindrops dripping from tree leaves high above play a low staccato tune on water beneath the boardwalk. Occasionally frogs croak, sounding like tightly plucked rubber bands.

Look skyward and you may see bald eagles, hawks or owls. Scurrying along the ground are feral pigs, deer, salamanders and, occasionally, a bobcat. An intriguing sight to be found here is the hundreds of cypress knees, some over five feet tall.

Congaree Swamp has been designated an International Biosphere Site, an area which preserves genetic diversity and provides an environmental baseline for plant and animal monitoring. The designation is appropriate: Congaree National Park is home to 700+ species of plants, 41 different kinds of mammals, 24 reptile species, 52 varieties of fish and 167 bird species.

To some people, Congaree National Park doesn’t have the awe of the Grand Canyon or the magnificence of Rocky Mountain National Park. But this unit of the national park system, located along the Congaree River in central South Carolina, is beautiful in its own right. “It’s a subtle beauty,” park ranger Fran Rametta observes. “The deeper in it you go, the more immersed you get.” Rametta enjoys walking through the forest and seeing things as they were 10,000 years ago. “I tell children it’s like walking through a time machine,” he observes.

The broad, muddy waters of the Congaree River furnish the swamp with the nutrients and moisture that enable trees to reach extraordinary sizes and age.

Congaree National Park today receives about 130,000 visitors a year–well below visitation of the Smoky Mountains or Yellowstone Parks–but not bad for a South Carolina locale whose charms are much more subtle, but in their own way, as impressive.

If You Go

In the National Park, you can walk six trails, from 0.7 mile to 11.1 miles. None of the walks is difficult because elevation in the park varies only about 30 feet. Most of the Congaree River can be paddled, as can Cedar Creek.

Visiting a swamp requires a keen sense of timing. What you ideally want are dry winter days, between November and March. If you go after rainfall, the Swamp is likely to be flooded. If you visit during the summer, you will encounter chiggers and mosquitoes, as well as snakes.

In spite of challenges, every season offers beautiful scenery and a different wilderness experience. The park’s massive trees provide a natural canopy and air conditioning, so summertime visitors will find respite from the stifling heat and humidity of paved city streets and parking lots. After the leaves fall, there is an openness to the forest that isn’t present any other season. No matter when you visit you are sure to be inspired by the subtle, yet stirring beauty. The park is open daily 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. For more information write the Superintendent at 100 National Park Road, Hopkins, SC 29061, or call 803-776-4396.

Follow us for the latest news!