Salmon have been swimming upstream to lay their eggs throughout the mountainous archipelago nation of Japan for thousands of years. The ruby-red eggs and succulent pink flesh of these powerful swimmers are more than just a source of delicious protein. The caught fish have provided tax revenues for emperors and feudal lords, served as New Year’s gifts, paid for schools, and become symbols of various regions. Salmon are imparted with a special cultural status in the northern Japanese city of Murakami, Japan.

Murakami natives clean the salmon, rub their bodies with salt, and hang the fish head downward with their mouths open. Salmon dangle from the eaves of markets, homes, restaurants, hotels, and the local salmon museum/hatchery/park. Powerful winds that sweep across the Sea of Japan are said to increase the flavor of the flesh. They are being air-dried, a preservation technique that goes back longer than anyone can remember.

Paying taxes in Japan with salmon also has a long history. Pamphlets distributed at the museum of salmon in Murakami, point out that local salmon were sent as tax to the Emperor of Japan around 900 A.D. In the early 1600s, the daimyo, or feudal lord, of Murakami also used salmon as a source of revenue. The lord sold the rights to fish within various sections of the Miomote River, which curves through Murakami. The fishing rights reportedly brought in more than 350 gold coins in one year, a tremendous sum at that time. To prevent overfishing and loss of revenue, salmon fishing was forbidden within certain areas. The lord rewarded people who informed on salmon poachers with silver.

Paying taxes in Japan with salmon also has a long history. Pamphlets distributed at the museum of salmon in Murakami, point out that local salmon were sent as tax to the Emperor of Japan around 900 A.D. In the early 1600s, the daimyo, or feudal lord, of Murakami also used salmon as a source of revenue. The lord sold the rights to fish within various sections of the Miomote River, which curves through Murakami. The fishing rights reportedly brought in more than 350 gold coins in one year, a tremendous sum at that time. To prevent overfishing and loss of revenue, salmon fishing was forbidden within certain areas. The lord rewarded people who informed on salmon poachers with silver.

For years, the salmon supported the economy of Murakami. However, within a short time, overfishing and habitat destruction resulted in such a decline in the salmon harvest that the once prospering Murakami fell into dire straits. In 1736, the lord of Murakami received only five gold coins. Poverty increased as well as poaching of the small number of salmon that were still returning to the Miomote River. The salmon population was decimated, and it appeared to be the end of the Murakami salmon runs.

For years, the salmon supported the economy of Murakami. However, within a short time, overfishing and habitat destruction resulted in such a decline in the salmon harvest that the once prospering Murakami fell into dire straits. In 1736, the lord of Murakami received only five gold coins. Poverty increased as well as poaching of the small number of salmon that were still returning to the Miomote River. The salmon population was decimated, and it appeared to be the end of the Murakami salmon runs.

Enter an inquisitive and environmentally aware samurai named Aoto Buheiji. Given the duty of restoring the salmon population, he took countless trips up and down the length of the twenty-five-mile long river, researched areas where the salmon spawned and compared those with places that the salmon did not spawn. He interviewed old people who lived along the riverbanks, as well as fishermen, and reviewed all the available records of salmon that he could get his hands on. Murakami credits him with being the first to report on the fact that salmon return to the same location to spawn. Using this knowledge, he came up with a controversial plan to increase the scant spawning salmon to previously recorded numbers.

Buheiji’s research led him to create the tanegawa-no-sei, (Tane means seed, gawa is river, and sei conveys the idea of sex.) a unique conservation system that has since been implemented in numerous Japanese rivers and rivers in other countries. First, based on his accumulated knowledge, he designated sections of the river as protected areas for spawning. He ordered fences to be constructed in the river to prevent salmon from passing beyond those areas. The restricted salmon eventually spawned in those areas that Buheji selected for having optimal spawning conditions. Fishing in those areas was prohibited until after spawning season was finished.

Buheiji’s research led him to create the tanegawa-no-sei, (Tane means seed, gawa is river, and sei conveys the idea of sex.) a unique conservation system that has since been implemented in numerous Japanese rivers and rivers in other countries. First, based on his accumulated knowledge, he designated sections of the river as protected areas for spawning. He ordered fences to be constructed in the river to prevent salmon from passing beyond those areas. The restricted salmon eventually spawned in those areas that Buheji selected for having optimal spawning conditions. Fishing in those areas was prohibited until after spawning season was finished.

He also divided a part of the river into separate channels. Fishermen were allowed to catch salmon ascending one section of the divided river. Taking salmon from another channel became illegal. Harvesting in the salmon breeding channel was limited to only those individuals who had special permission to harvest the eggs for incubation purposes.

However, not all of the local people agreed with the plan. Many local fishermen and other residents were angered at being prohibited from using the resources of the river as they had done in the past. There were angry protests. Fights erupted between the conservationists and their opposition. Some opponents destroyed the fencing in the river, and others protested to high-ranking government officials. Buheiji was called to the nation’s capital for a meeting. After conferring with Buheiji, though, the national government decided to support his controversial conservation plan.

However, not all of the local people agreed with the plan. Many local fishermen and other residents were angered at being prohibited from using the resources of the river as they had done in the past. There were angry protests. Fights erupted between the conservationists and their opposition. Some opponents destroyed the fencing in the river, and others protested to high-ranking government officials. Buheiji was called to the nation’s capital for a meeting. After conferring with Buheiji, though, the national government decided to support his controversial conservation plan.

He succeeded. The salmon returned in great numbers to Murakami. Buheiji’s work was so successful that the lord of Murakami in 1760 received 300 gold coins from taxes on the right to fish salmon. In 1859, the population rebounded so much that using the same taxation system, the lord of Murakami received 5,600 coins.

Buheiji spawned generations of salmon researchers. In the 1800s, locals established the Murakami Salmon Foundation, which experimented with artificial incubation. The foundation also introduced Chinook salmon from the United States. The salmon population kept increasing, and the salmon wealth was distributed among the residents.

Buheiji spawned generations of salmon researchers. In the 1800s, locals established the Murakami Salmon Foundation, which experimented with artificial incubation. The foundation also introduced Chinook salmon from the United States. The salmon population kept increasing, and the salmon wealth was distributed among the residents.

More than 700,000 salmon were harvested in 1884. The tax revenues and sell of salmon paid for schools and orphanages in Murakami. The orphans were nicknamed “salmon children.”

Regrettably, a changing social structure and development in the twentieth century caused a sharp decline in the river’s health. Only 10,000 salmon were caught in 1948. Miomote Dam, constructed in 1953, exacerbated the situation. The catch plummeted to just 1,000 in 1954. Fishing groups in Murakami put more effort into the hatching, raising, and release of salmon fry. The salmon harvest is now approximately 10,000.

On the autumn day that I first walked through the salmon park on the banks of the local Miomote River, Sparkling salmon splashed and churned in the shallow pebbly areas of the river, leaping upwards and forward, straining to overcome barriers in their way. A fisherman stood in a knee-high section of crystal water. Grey and white herons stoically waited for fish to come near. Crows, commenting on the action, noisily squawked. Hawks flew in spirals above the rushing water, occasionally swooping downward to the surface. Within the river, there was a salmon trap. The trapped salmon would be taken to the hatchery at the nearby salmon museum. We stayed until the sun set in the horizon and strolled back through the autumn woods towards the museum.

On the autumn day that I first walked through the salmon park on the banks of the local Miomote River, Sparkling salmon splashed and churned in the shallow pebbly areas of the river, leaping upwards and forward, straining to overcome barriers in their way. A fisherman stood in a knee-high section of crystal water. Grey and white herons stoically waited for fish to come near. Crows, commenting on the action, noisily squawked. Hawks flew in spirals above the rushing water, occasionally swooping downward to the surface. Within the river, there was a salmon trap. The trapped salmon would be taken to the hatchery at the nearby salmon museum. We stayed until the sun set in the horizon and strolled back through the autumn woods towards the museum.

As we walked by the outside of a fish shop near the museum, a man was taking glittering salmon from a tub and rubbing white salt into the flesh. The salmon had just been caught. He was preparing them to be hung from the eaves of the museum. Their skin flickered under the strong outdoor lights. I watched for a few minutes. Looking down, I noticed a manhole in the street. An image of a salmon was etched into the metal.

The salmon museum is on the grounds of the salmon park, which has walking paths along the river. Tour the museum to study the history of salmon in Murakami. It is a wonderful place to learn about salmon biology and the major cultural importance given to one species of fish.

The salmon museum is on the grounds of the salmon park, which has walking paths along the river. Tour the museum to study the history of salmon in Murakami. It is a wonderful place to learn about salmon biology and the major cultural importance given to one species of fish.

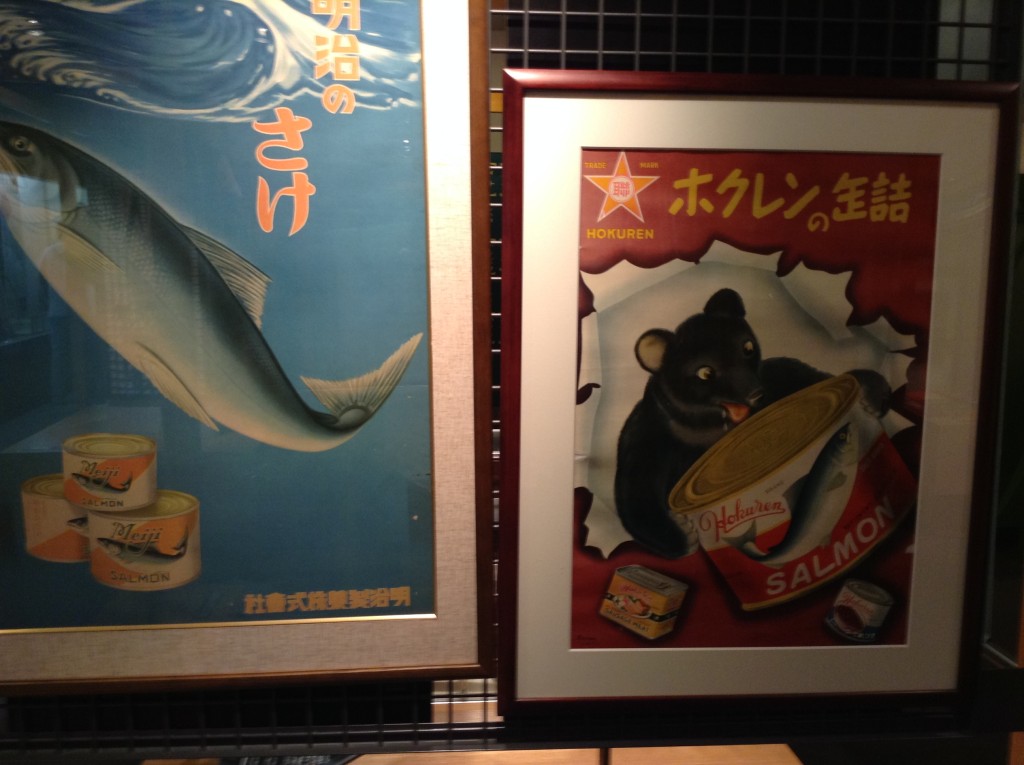

A hatchery shares the grounds with the museum and hatchery exhibits explain the cycle from egg to fry to salmon. Salmon at various stages of development swim in small aquariums or in wide tanks. Within the connected building, cultural trends in art and eating habits are reflected in the museum exhibits of decades of advertisements for salmon and salmon products. Salmon displays in the museum also include shoes, hats, and a jacket made from the skin. Tools for catching salmon, such as nets, traps, and spears, date back many hundreds of years. Faded black and white photographs of locals catching salmon stretch from the beginnings of photography in Japan to colorful images of modern life.

In mid-December, I strode past the salmon museum to the Miomote River to see locals catching salmon in river sections where salmon fishing is permitted to those with permits. Swimming and spawning salmon were stirring in the water. The icy river banks held chewed and pecked at carcasses of fish that had spawn and naturally expired. Despite the 1C outdoor temperature, well-bundled fishermen were standing or sitting on the river banks with four meter or longer fishing poles and tossing lines with treble hooks into the clear water.

In mid-December, I strode past the salmon museum to the Miomote River to see locals catching salmon in river sections where salmon fishing is permitted to those with permits. Swimming and spawning salmon were stirring in the water. The icy river banks held chewed and pecked at carcasses of fish that had spawn and naturally expired. Despite the 1C outdoor temperature, well-bundled fishermen were standing or sitting on the river banks with four meter or longer fishing poles and tossing lines with treble hooks into the clear water.

Most of the fishermen were past retirement age, but one grandfather had his grandson by his side. After his grandfather pulled in a five-kilogram male salmon, the boy proudly held it up for me to photograph. The boy was learning the salmon culture from his grandfather. Hopefully, the grandson will also learn to protect the environment, so his future grandchildren can continue the tradition of salmon fishing in Murakami.

Leave a Comment